"Art is the one thing an American person can pursue that has nothing to do with power."

Poet Lizzie Harris shares how the best gift she’s ever received helps her relive her punk band days. Plus, her Park Slope muffin obsession.

Thanks so much for reading Park Slope Times! I’m Kelley MacDonald, and each week, I interview an interesting person about their life and favorite things to see, eat, and do around Park Slope. If you'd like to read these interviews, please upgrade to paid. If you stick with a free subscription, you'll receive occasional free emails. Thank you so much for being here!

Reading via email? You may need to click “view entire message” to see the entirety of this week's issue.

Hi! How’s your week going? Did you notice there wasn’t a newsletter last week? I managed to come down with a terrible cold and was sick for a week, coughing, sneezing, and the worst part — a bad sore throat. AND my laptop died! So, I had to skip last Friday’s issue, but I’m really excited to share today’s interview with poet Lizzie Harris!

“I really don’t think of poetry as work. It is my method of digesting and processing the world; it’s my method of thinking,” says Lizzie, who earned her MFA from New York University. Lizzie’s debut collection, “Stop Wanting,” came out in 2014, and she’s currently writing her second collection about the tension between capitalism and motherhood, intimacy and virtual existence. Her poems have appeared in The New Yorker, VICE, Cordite Review, PANK, The Offing, Painted Bride Quarterly, DIAGRAM, and many others. Lizzie is also a Senior Partner at Lippincott, a brand strategy and design company, where she focuses on helping businesses build out emotionally intelligent communication practices. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband and two young kids.

In this interview, Lizzie shares the moment she knew she wanted to be a poet, why she decided to pursue a career outside of literary art, and how her moving poem in The New Yorker, “Law of the Body,” came to be (“I got really mad.”). She also tells us where to find cheese fries that are perfect if you’ve had a “shit day,” plus great yeast donuts and a swim school for kids.

Hi Lizzie! So, you were raised in Pennsylvania; what brought you to NYC?

I came here to get an MFA in poetry and then to teach at NYU. In a few months, it’ll be 15 years that I’ve been in Brooklyn. When I first moved here, I paid $600-$650 a month and lived on Classon Avenue. No one knew if it was Crown Heights or Prospect Heights; it was that in-between border. I lived with a boyfriend, and we had a railroad apartment and broke up maybe three months into being there. I lived there for nine months after we broke up, but it was way more tolerable than you’d think [laughs]. He ended up meeting his wife while living there, so there was good juju in that apartment.

Then I moved to — I guess you would call it Gowanus now — for half a decade. I’ve had the distinct honor of being in constant no man's land in Brooklyn. The year I moved [to Gowanus] was when they started building those giant condos, and then, The Whole Foods went in. It was very quiet. I watched that neighborhood change so crazily. I remember nights walking home from the subway, and I’d be walking behind a raccoon — literally wildlife owned the streets [laughs]. It was just empty, and it's obviously a really different neighborhood now. But I just followed where the cheapest rent was, and I lived in loft-style apartments with four, sometimes five, people.

Did you work in the area?

I worked at this place called Bark Hot Dogs in Park Slope for about two years when it first opened. It was my second waitressing job in New York, and we sold these bespoke, farm-to-table hot dogs. The executive chefs are lovely people, but it was very overpriced and peak Park Slope parents’ bait at the time. This was 2010, and it was a $9 hotdog! It was [featured on] The Food Network, so we’d get tourists, and we had our regulars. We’d also get a very bougie Park Slope parent, and that was my first introduction to the ethos of that. I got to be a fly on the wall of what that family makeup was. I remember thinking, You guys are fucking cool! They were letting their kids kind of run around, telling them to do their own thing, while they were drinking a beer and talking shit with their friends. There was chaos around them, but it was so glamorous to me. That was when I thought I could really stay here and be that. I was in my mid-twenties and [trying to figure out] how to make Brooklyn work forever.

Was there a specific moment when you knew you wanted to be a poet?

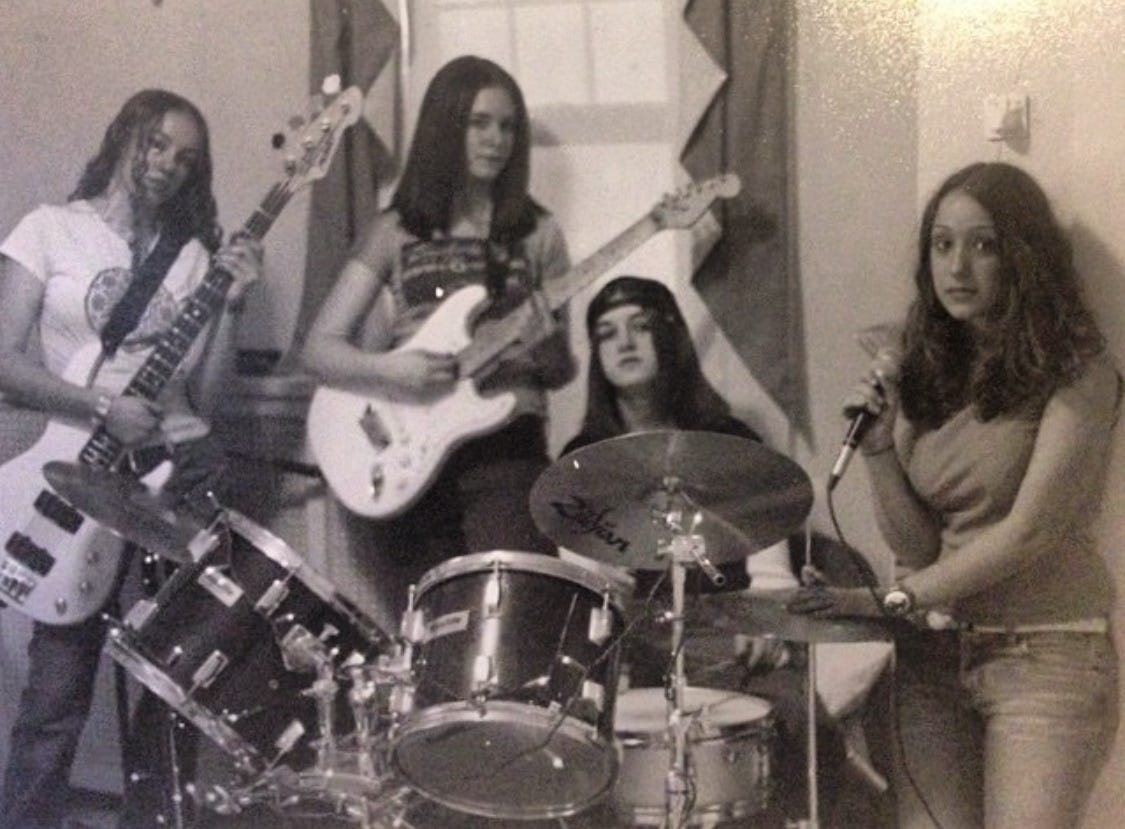

I know the exact moment. I was sort of a shit student, a C, C- student in high school. I never found the thing that felt like my vernacular; I didn't have that experience of having a subject or a topic that clicked and made me feel smart. I think a ton of people are like this because there are only so many things you’re exposed to in high school. But I was in a punk band at the time, and I thought, Ohhh, maybe I’ll take a poetry class. I love writing lyrics.

So, when I was [at the University of Pittsburgh in 2005], I took a class with this amazing poet named Lynn Emanuel, who is just an absolute icon. I remember having office hours with her after I'd written my first or second poem, and she’d given me good feedback. She assigned books, but I was so broke that I couldn't buy them, so I would read them in the library. I couldn't take them out of the library and had to read them there. There was this Ilya Kaminsky book called “Dancing in Odessa,” and I picked it up, read the first page, plopped down in the stacks, and read the book cover to cover. And then I went back and read it cover to cover again. By the time I was in class with Lynn the next week, I had poems memorized. I was like, Oh shit — this is my language. This was the moment I felt like I got something intuitively, and it wasn’t an arduous task.

Lynn has this amazing way of not taking people seriously, which makes when she takes you seriously really amazing. Assuming that I was going to push through poetry, she said to me, “Do you want to be a poet? Of course, you want to be a poet. What else is there to be?” At that point, it became this fever dream — the thing that I love.

Wait, I need to know more about your punk band!

Oh my god. It was called The Curves. It was all women. I was in it from the time I was 12 to 16 or 17. I sang, but I always wanted to play the drums, and our drummer always wanted to sing. Most of the time, when we were practicing, I'd be playing around on the drums and she would be singing and harmonizing. I've always wanted to be a drummer, but no, I screeched.

Did you write your own songs?

We did. That was my first foray into writing. My best friend, we’re still best friends today, Rachel Nagelberg Ackerman, was great at guitar, and we started writing songs when we were 11 or 12. We would record them on the computer, practice, and get good at them. We probably wrote 30 songs together over the decade or so of being teenagers. Now, sometimes when we're having a bad day, one of us will extend the other a really embarrassing lyric or something.

Did you ever consider staying and teaching in higher education?

It's so funny — I was just talking to my husband about this. There was this moment where it was like, what's the urgency here? And the urgency for both of us — and I think why we were able to make a life together — was staying in New York. That felt more important to our interior lives, our social lives, and our literary lives than teaching did at the time. So we both got writing adjacent, more structured jobs because it was all about sustaining being in this place. If you can build a life in New York, no matter what that life looks like, you will always be able to go to a reading at night or walk to one of 10 amazing used bookstores.

And I think you can absolutely be a writer and have an amazing rich literary life outside of New York. I hate when people pretend that's not a possibility, but I think for us, we knew [living here] would be the closest to what we wanted. And so yeah, the notion of being a teacher was something I really loved, but it wouldn’t keep me here the way I wanted. I grew up very, very, very lower middle class, and I was financially independent by the time I was 17, so I had to do something that could sustain [my lifestyle]. I was very cognizant that it was going to be this trade-off. The price of staying in New York for me was sacrificing my dream job for my dream life — the life I want outside of work.

As someone who produces literary art consistently and has a full-time job separate from your art, what advice do you have for people trying to figure out if their art can be their full-time job, if a different day job is right for them, or some combination of the two?

This is such a good question. I think there are two things you can do if you really want to be an artist. You can either become a careerist about your artistic pursuit and try to monetize it, or you can be an absolute purist about what that practice means to you and find another way to make money. I guess the third option is you come from money, which god bless.

For me, it comes down to this preservation of what poetry is to me. It’s my beloved; it's this thing that punctuates my life. It’s what I look for every time I go to a city, every time I process an event. And that sounds pretentious, but what it means is I would not be very good at knowing how to monetize it. I have incredibly successful writer friends who make their entire income off of writing, and they don't take it any less seriously — of course not — but they are comfortable not preserving it. And I think I'm a little idealistic about it. So, for me, poetry is about the process, about doing the work. Not about the publishing of it, the scale of it, or the creation of a personal brand.

In my mind, art is the one thing an American person can pursue that has nothing to do with power. It doesn’t have to innately have something to do with capitalism. So, to me, the radical act of committing my life to something that never rewards me [laughs] means I know where I stand. I know what it is to me. I’m not asking for it to return something to me other than my sanity [laughs] and my ability to stay in myself. So that for me is why the two could diverge really quickly.

Sometimes, we think we can’t have both — can’t create the way we want to and have a successful job at the same time — but you’re proof that we can. So, I’m curious: where do you write, and how do you get all your writing done?

My favorite place to write changes, you can't be precious about it. It used to be the subway or the bus, and I would get quite a lot of writing done. But now I only go into the office two to three times a week. So, right now, my favorite time to write is actually during bedtime. My daughter has this horrible regression where she needs me to be in the room to fall asleep, so I just sit in the corner and write, and she falls asleep. It yields domestic poems. I like the idea of not trying to stage your creative process, but actually being honest about where it can exist in a sustainable way in your life. Because that makes the work more reflective of your actual life, and I think less performative.

In grad school, I could go to a coffee shop and write. It was very different than what I write now. My life doesn't look like that now, and even if I could race to a coffee shop and write for a few hours, I'm not sure it would be the poems I need to be writing right now. The most consistent thing about my personality is I love limitations. I love restrictions. I love the structure of my life telling me where and when I have permission to be creative. The busier I am the more present I can be with each task. Then it’s about forcing myself to use that time instead of brainlessly scrolling the way I would love to or watching people chop onions on the internet, which I love to do.

Do you write with pen and paper or on your phone or computer?

I like to write mostly in my head, and by the time I put something down, it's not done but it's a full first draft. I’ll suddenly start to get some urgency, and usually, I take out my Notes app and write it all down in one go. A lot of the time I will write on pen and paper as I'm forming an idea and forming the world of the poem. But the first thing I do is I put it in my Notes app, and then I text it to my husband.

Your poem “Law of the Body” is so powerful and moving. What was the writing process like for that piece?

The way that came to be was the leak happened [overturning Roe v. Wade], and I was in a meeting and everybody started texting me. I just started freaking out. I had just had an incredibly terrifying labor with my second where I was accidentally overdosed, and my blood pressure dropped. I was unconscious for about an hour and had an emergency C-section. We got to the point where in between moments of consciousness, I was telling my husband what to say to our daughter. It was really scary. The fact that I was still in recovery, emotionally and physically, from that and to see that [leak] felt like this incredible erasure — not just of women’s autonomy — but even with autonomy what women fucking sacrifice for society every day. And not just through labor and motherhood but in all of the other incredible ways that women contribute in spite of this constant limitation placed on them. So, I got really mad. I took out my Notes app, and I wrote that poem in probably five minutes. I texted it to my husband, and he texted me back, “Send it to The New Yorker.” I actually thought that was sort of silly because I didn’t know if [the poem] would have any value on a platform that big. But I promised him I would.

When I heard back from [The New Yorker poetry editors], I probably screamed louder than I have ever screamed in my entire life. My husband was bathing our kids, and I just started hyperventilating and screaming. He ran out and said, “Is it a rat?” I couldn’t speak.

It’s definitely my most widely-read poem ever. And holy shit…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Park Slope Times to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.